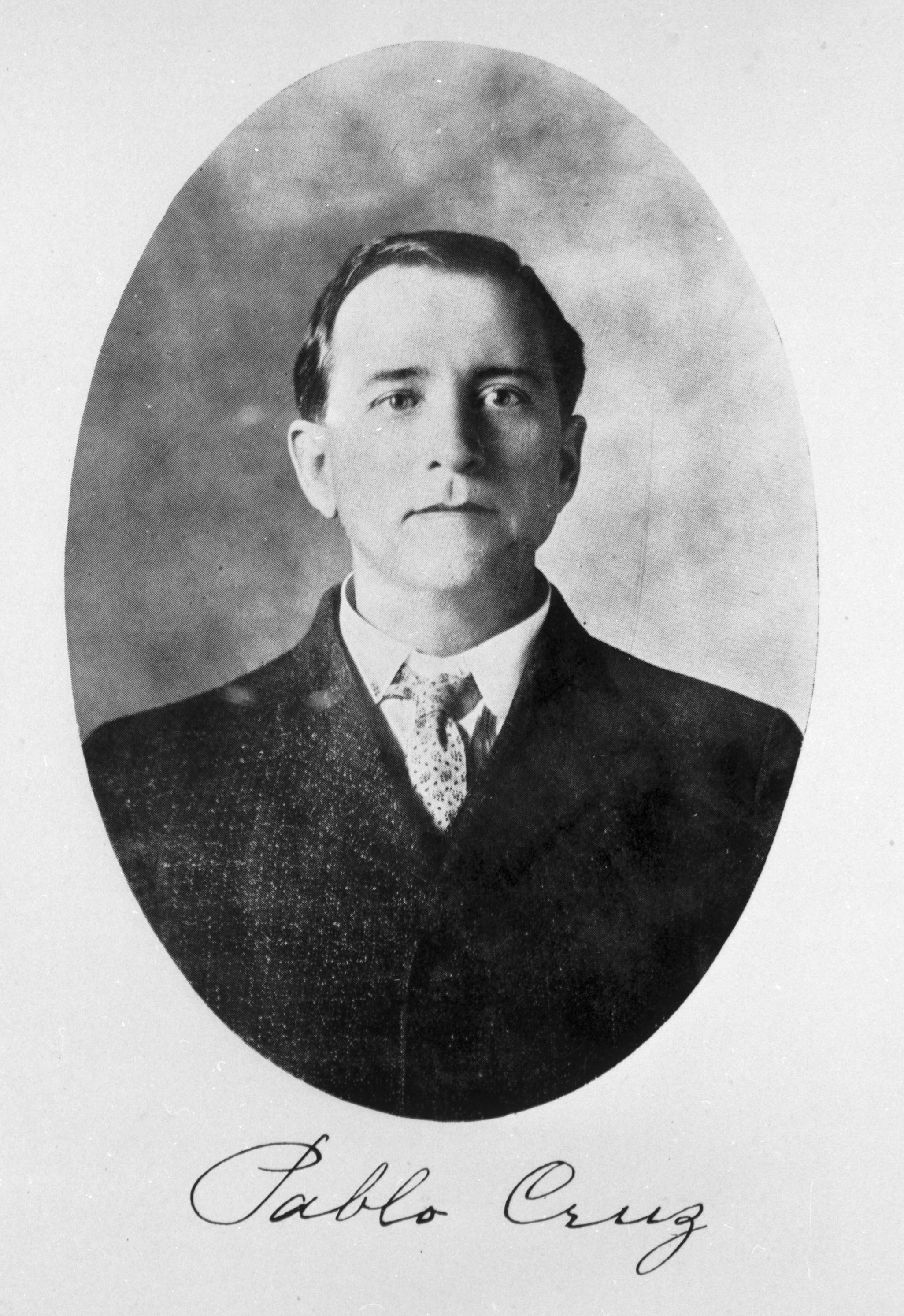

Pablo Cruz: A Laredito Bookseller

This week’s post features guest blogger Emiliano Calderon, a staff member at Casa Navarro State Historic Site, located in downtown San Antonio.

by Emiliano Calderon

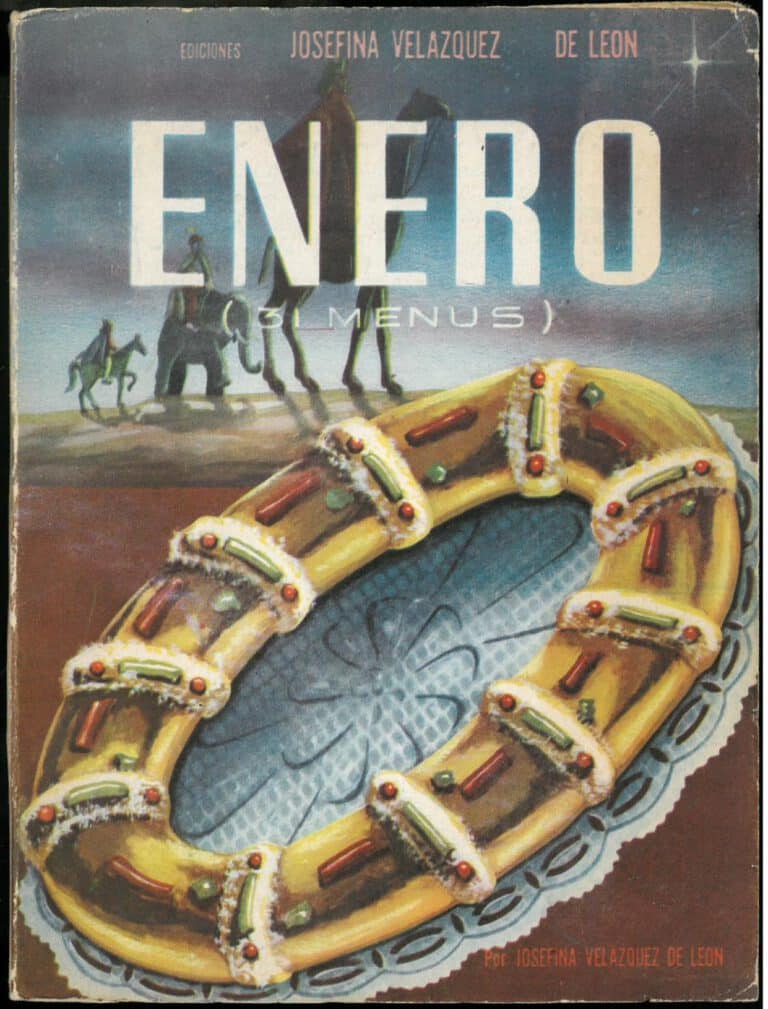

While working on our historic foodways programs at Casa Navarro, Juli McLoone brought to my attention a series of cookbooks that were being sold in San Antonio at the turn of the 20th century. She had come across an advertisement for La Cocina en el Bolsilla in a December 23, 1897 issue of El Regidor. According to the advertisement, the books were being sold for ten cents each by Pablo Cruz at 406 Matamoros Street.

Previous knowledge of San Antonio’s historical geography indicated to me that the street address was in close proximity to Casa Navarro, former home of Jose Antonio Navarro, a resident of San Antonio’s Westside. This made me curious about the seller of the books as I was seeking to make a connection between the cookbooks and the history of Navarro’s neighborhood. Beyond realizing that our Westside bookseller was in fact the publisher and printer of El Regidor, a review of sources available at the Texana Room in the San Antonio Public Library provided me with a glimpse into the public and private life of Mr. Cruz.

San Antonio was the center of commerce, industry and trade in nineteenth century Texas. The cosmopolitan feel of the city created a vibrancy and setting unique to Texas both then and now. The three largest ethnic groups residing in the city were Germans, African Americans and Spanish-Mexicans, although a number of other groups including Italians, Chinese, and French were also present.[1] The influence of the Spanish speaking community in the city was irrefutable as it had the longest presence dating back to seventeenth century when Canary Islanders and Mestizos began settling the area.

The families of the Canary Islanders were among the most prominent members of the community in seventeenth and eighteenth century San Antonio, often times expressing a dual Tejano and Mexicano identity through religious and cultural activities alongside their working class counterparts. The plazas and west of the San Antonio River were the focal point of these cultural celebrations such as Cinco de Mayo (Commemorating the Battle of Puebla), the feast of our Lady of Guadalupe, and Los Pastores (Nativity Play). Likewise, the Westside plazas were the center of market activities where vendors sold their produce, goods and services both day and night.[2]

In the decades following the American Civil War, Tejanos and the Spanish Mexican Elite of San Antonio experienced a downward trend in social mobility. Increased Anglo immigration, and decreases in intermarriage between Tejanos and Anglo or European families and overall immigration from Mexico hardened an ethnic boundary that largely confined the Spanish-speaking community to neighborhoods west of the San Antonio River.[3] In this Texas-Mexican cultural landscape shops and homes made of adobe, cedar and sometimes brick lined the streets of San Antonio’s Westside providing spaces for families and businesses to operate throughout the area. The shop owners that often lived with their families in attached or detached dwellings were the precursors to the middle class of San Antonio’s Westside that developed in the 1920’s and 1930’s.[4] However, it should be noted that a majority of the Mexican middle class had immigrated to San Antonio as a result of the Mexican Revolution, when immigration from Mexico increased dramatically.[5]

Pablo Cruz was born in Monclova, Coahuila, on February 8, 1866 to Abraham Cruz Valdez and Viviana Cardenas de Cruz. Cruz remained in Mexico until 1877 upon moving with his family to Floresville, approximately 30 miles south of San Antonio.[6] It is unclear as to why the Cruz family moved to Floresville although it is plausible the move had to do with the tremendous need for labor associated with Texas’ growing economy since he was listed by the 1880 U.S. Census as working at a dry goods and shoe shop.[7] Cruz lived in Floresville for the next five years before moving to San Antonio and later establishing El Regidor in 1888. The J.A. Appler’s City Directory from 1897 listed 410 Matamoros Street as being Cruz’s print shop, with an attached address of 406 Matamoros as being the residence of Cruz. This building was a one-story structure with an attached dwelling and porch located just off the Matamoros Street and Pecos Street intersection, then the far west reaches of San Antonio’s Westside, and was surrounded by numerous small homes and other businesses including a blacksmith shop, a warehouse and a camp yard.[8] Presently, this area is the Durango street parking lot of UTSA’s Downtown Campus.

Cruz was living and working out of this address along with a sizeable family including 4 children, a nephew, and his wife Zullema whom he had married in 1892. It was evident the Cruz household was a well-educated one, as he and his wife were listed as being able to read, write and speak both English and Spanish, while his eldest daughter, Sarah was listed as learning both languages and enrolled in school along with their eleven year old nephew Pedro Garcia.[9]

As early as 1904 Cruz had a 2-story brick building constructed for his printing, publishing and book sales operations located just off the intersection of South Laredo Street and Dolorosa Street.[10] Characterized as a buffer zone between the Anglo and Mexican sides of town, the blocks surrounding Cruz’s new shop were filled with structures built of brick, adobe or wood, standing at single or two stories tall and utilized as dwellings, restaurants, stores, and shops for everything from metal working to tortilla making. Coincidentally, Jose Antonio Navarro’s home was erected on the same block of South Laredo Street approximately 50-60 years earlier. The two adobe buildings once occupied by Navarro and his family were then being utilized as dwellings while the two-story mercantile building functioned as a store. Across Nueva Street, where the statue of Jose Antonio Navarro currently stands, stood a saloon.[11]

Mr. Cruz moved with his family to a home at 442 Dwyer Avenue in 1906. This larger home was located on the west bank of the San Antonio River directly north of the United States Arsenal. The street and neighborhood surrounding the residence was of mixed upper and middle class income due to the large number of single family homes that stood one to two-stories, and the detached garages or servant’s quarters in their expansive backyards.[12]

San Antonio’s Westside was notable for the number of Spanish Language newspapers it produced at the turn of the twentieth century. Perhaps the most famous of these was ‘La Prensa’, established by Ignacio E. Lozano in 1913, which functioned largely as the mouthpiece of exiled supporters of the Porfirio Diaz government in Mexico. Likewise, it was the location of Paulino Martinez’s print shop located east of Milam Square Park on Santa Rosa Street, where Francisco Madero’s infamous ‘Plan de San Luis Potosi’ was printed. Although many of the newspapers and editorials coming from San Antonio’s Westside were concerned with Mexico, it is possible that El Regidor was much broader in scope of the issues and news it covered due to the role the newspaper and Cruz played in the arrangement of the legal defense fund for Gregorio Cortez, the Mexican Texan folk hero accused of murdering several South Texas law enforcement officers in 1901.[13]

Despite the absence of a newspaper distributed state-wide, poor roads and few cars, Cruz through El Regidor, began taking up collections to pay for the defense of Gregorio Cortes in the courts and was responsible for the hiring of attorneys for multiple trials and mistrials that would follow. The network of worker’s societies, editors, women and everyday individuals that participated in the fundraising efforts for Cortez represented one of the first times mobilization of the Mexican and Texas Mexican community took place on a large scale, and across international boundaries. The effort laid the foundation for a 1911 statewide conference in response to the lynching of Texas Mexicans, known as the Primer Congreso Mexicanista.[14]

Americo Paredes, in ‘With his Pistol in his Hand’, acknowledges this and uses his study of Ballads or Corridos associated with the Cortez incident to demonstrate the level of Cruz’s involvement with the defense fund movement. He notes a Mexico City broadside distributed to raise funds in which Gregorio Cortez, through the ballad singer, speaks directly to the audience.[15]

‘Pablo Cruz distinguished himself, as an upright Mexican, the prominent brother, who gave me his aid. I make tis news known, to honest and cultured people, those who put themselves on this numbered list – may fortune be kind to them.’

Ultimately, Cortez was imprisoned on horse theft charges, but released in 1913 under a conditional pardon by Texas Governor Oscar Colquitt. Paredes notes that Cruz was involved with the legal defense of Cortez until his death 1903. However, I believe this may have been in error since his obituary is not printed until 1910.[16] Either way, he did not live to see the final release of Cortez.

Pablo Cruz died sometime between August 5th and August 12th of 1910 while on a trip to Los Angeles. The 1920 United States Census lists Zullema Cruz as the Head of Household for the Dwyer Avenue home following the death of Mr. Cruz., Pablo Cruz Jr., Cruz’s eldest son, took over the publication of El Regidor following the death of his father, and later went on to be one of the founding members of The Order of the Sons of America in 1921, a middle class Texas Mexican civil rights organization that preceded the founding of the League of United Latin American Citizens. The organization headquartered in San Antonio fought against racial discrimination through the criminal justice system and ranged in membership from 50 to 250 persons cooperating with the Mexican consulate, and workers’ mutualistas until its demise several years later.[17]

Casa Navarro is located at 228 South Laredo Street in downtown San Antonio, along the Texas Independence and Hill Country Trail Regions.

[1] Garcia, Richard. Rise of the Mexican American Middle Class. College Station: Texas A&M University Press, 1991. Pg. 17-18.

[2] Garcia, 20-21

[3] Garcia, 22-23.

[4] Garcia, 21-22

[5] Ibid.

[6] A Twentieth Century History of South Texas, Volume 1. New York: Lewis Publishing Company, 1907. Pg.438.

[7] United States Census, 1880. Abram Cruz, Floresville, Wilson, Texas, United States.

[8] Sanborn Perris Maps Company. Insurance Maps: San Antonio, Texas. New York, 1896.

[9] United States Census 1900, Pablo Cruz, San Antonio, Bexar, Texas, United States.

[10] Davis, Ellis A, and Edwin H. Grobe, Eds. The New Encyclopedia of Texas. Dallas: Texas Development Bureau, 2237.

[11] Sanborn Perris Maps Company. Insurance Maps: San Antonio, Texas. New York, 1911.

[12] Sanborn Perris Maps Company. Insurance Maps: San Antonio, Texas. New York, 1912.

[13] A Twentieth Century History of the Southwest, 438.

[14]Orozco, Cynthia. No Mexicans, Women or Dogs Allowed. Austin: University of Texas Press, 2009. Pg. 69, 70-71.

[15] Paredes, Americo. With His Pistol in His Hand. Austin: University of Texas Press, 1970. Pg. 87-89.

[16] San Antonio Light & Gazette. August 5, 1910, pg.7. San Antonio Light & Gazette. August 10, 1910, pg.13. San Antonio Light & Gazette. August 12, 1910, pg.15.

[17] Orozco, 73-77.