Papadzul 1970 (Pumpkin Seed Enchiladas)

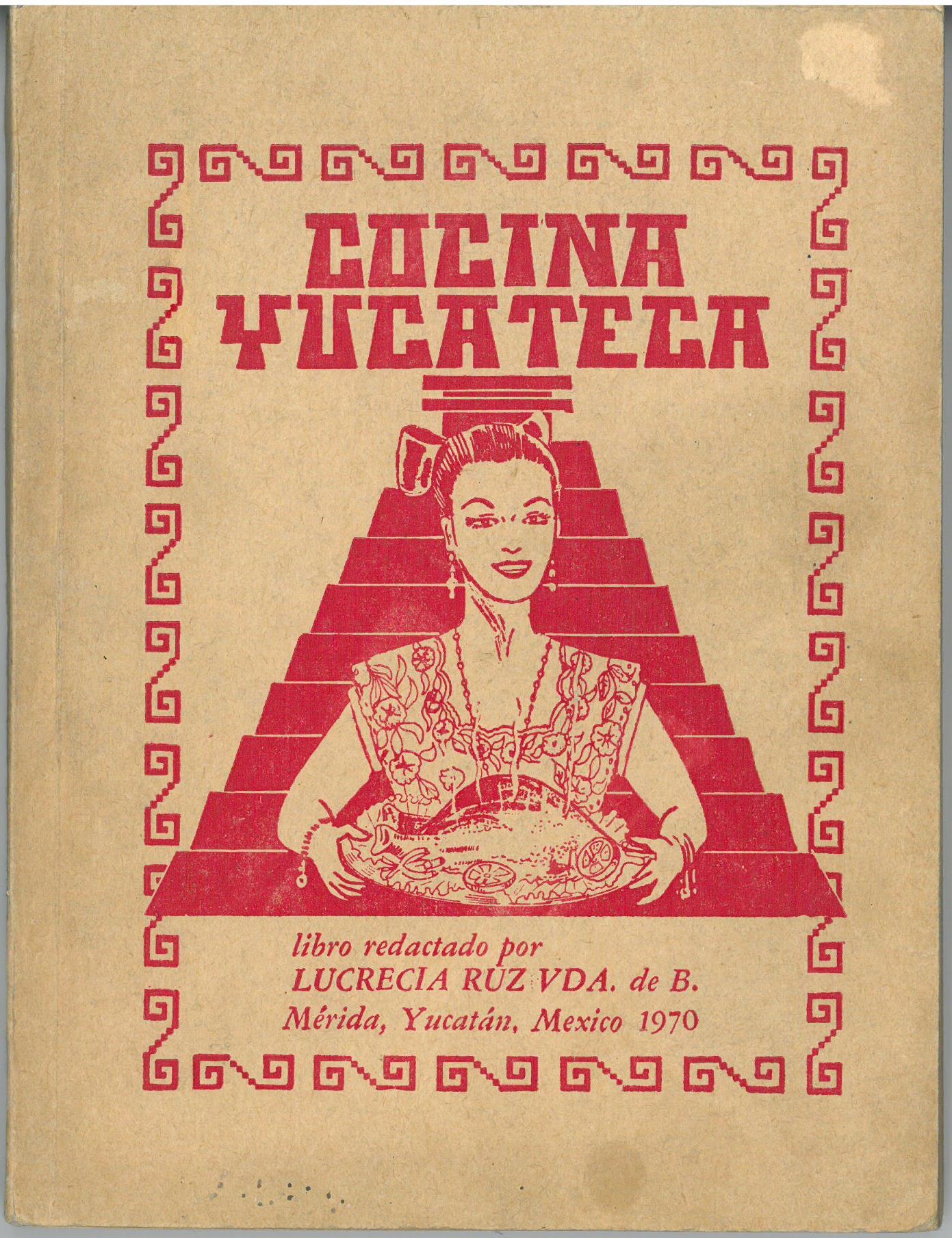

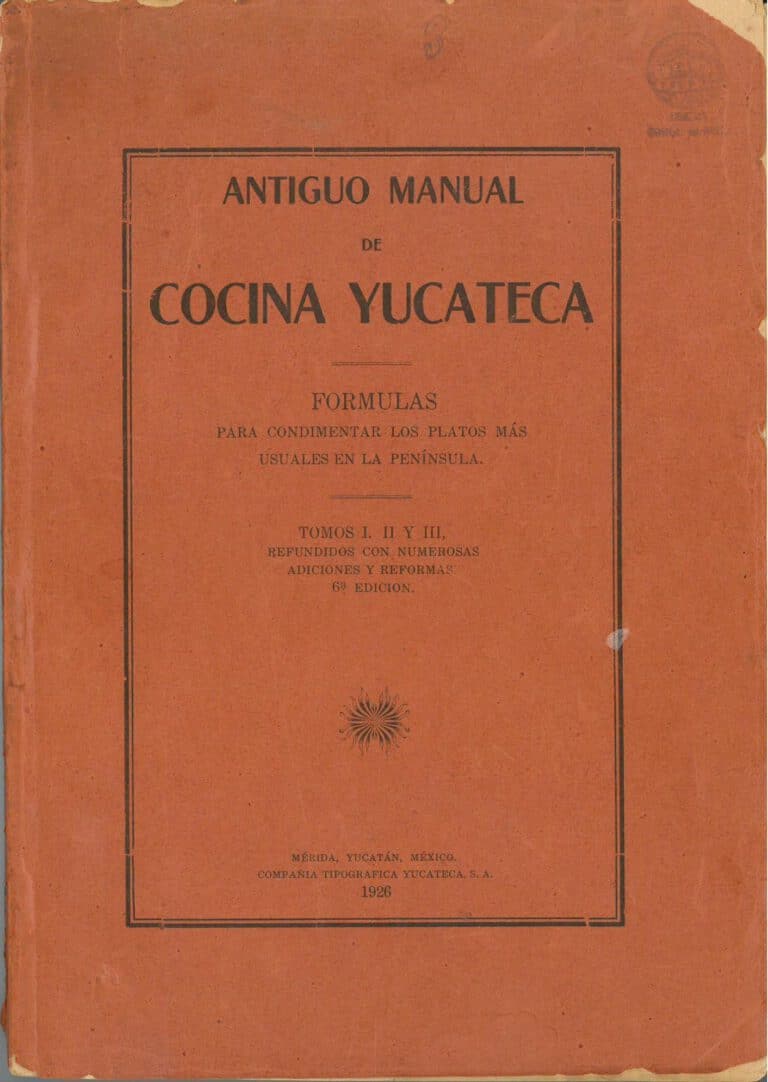

Ruz Vda. de Baqueiro, Lucrecia. Cocina Yucateca. Mérida, Yucatán, México: s.n., 1970. [TX716.M4 R89 1970].

Last week, we introduced Lucrecia de Baqueiro’s Cocina Yucateca. Originally published sometime prior to mid-century (probably in the 1940s), de Baqueiros’s work remained popular for decades, as evidenced by UTSA Libraries’ copy of the 8th edition, published in 1970.

This edition includes chapters on Sopas / Sopas, Mariscos / Seafood, Aves / Poultry, Carnes / Meat, Huevos / eggs, Pates y Piernes / Spreads and legs, Tamales, Dulces / Sweets, Panes / Bread, and Helados / Ices.

The chapter on Pates y Piernas includes an interesting mix of dishes. As expected, it contains numerous paté recipes, most of which build from a common base of beef, pork, ham, and nutmeg, and add various other ingredients to differentiate the recipes. Pate sin Rival, for example, adds potatoes and vinegar, while Pate de las Estrellas adds cheese, jalapeños, onion, mayonnaise, and milk.

When first looking at the recipe title, I assumed that “Piernas” or “legs” must be metaphorical. After all, why wouldn’t leg recipes be included in the “Carnes / Meats” chapter? To my surprise, “Pates y Piernas” does, indeed, include recipes for legs, such as Pierna de Puerco al Horno / Baked Pork Leg, Pierna de Puerco en Piña / Pork leg in Pineapple, and Pierna de Venado Enjamonada / Venison leg Ham. All of these leg recipes give instructions for serving cold slices on platters garnished with radishes, lettuce, etc. Perhaps the author felt that these recipes belonged conceptually with patés because both were intended for guests at luncheons, receptions, or light buffets.

The shared context of when and how these foods are consumed may also explain the third category of recipes that is (silently) included in “Pates y Piernas.” The chapter offers instructions for several antojitos — tortilla-based foods like taquitos and panuchos that are often served as appetizers. One of these recipes provides instructions for Papadzul, a traditional Yucatan dish similar to enchiladas in which corn tortillas are filled with hard boiled eggs and served with pumpkin-seed sauce.

Papadzul (p. 138)

- 1/2 Kg. de pepita gruesa pelada

- 1/2 Kg. de tomates

- 2 chiles habaneros

- 10 huevos

- 1 Kg. de tortillas

- 1 Manojo de apozote

- Sal al gusto

La pepita se tuesta ligeramente, sin dejar que se queme, y se muele en molino de chocolate para que salga bien espesa.

Los huevos se hierven; ya cocidos se pelan y se majan con tenedor.

Los tomates se hierven en litro y medio de agua con sal, chiles habaneros y apazote. Luego se escurren los tomates, se despepitan y se tamulan con su punto de sal.

Si lo prefiere pueden licuarse y luego preparar la salsa de tomate frita, con sus chiles habaneros.

La pepita molida se va rociando con el agua caliente donde se cocieron los tomates y se amasa suavamente, rociando las veces que sea necesario, hasta que suelte su aceite. Este aceite se recoje en una lacita y sirve para cubrir los taquitos.

Con el resto del agua donde se cocieron los tomates se deshace la pepita molida, con punto de sal, hasta formar una crema ligeramente espesa.

Las tortillas calientitas se remojan dentro de la crema de pepita, se colocan en un platón, poniéndole a cada tortilla en el centro huevo majado, se arrollan, se cubren con crema de pepita, salsa de tomate y encima el aceite que soltó la pepita.

Papadzul (p. 138)

- 1/2 Kg. shelled pumpkin seeds

- 1/2 Kg. tomatoes

Note: In Central Mexico, and thus in most Mexican cookbooks published in the capitol, “tomate” refers to tomatillos. However, in the Gulf coast states, and in the North and the Southeast of Mexico, it commonly refers to red tomatoes, while other terms (tomate verde, miltomate, etc.) are used to refer to tomatillos.[1] With that said, this recipe seems potentially ambiguous as it calls for boiling the tomates, a common method of preparing tomatillos, but not not, to my admittedly limited knowledge, tomatoes. The good news is that, although tomatoes and tomatillos taste quite different, most dishes are very tasty with salsa made from either one, so home cooks may take their choice. - 2 habanero chiles

- 10 eggs

- 1 Kg. tortillas

- 1 handfull epazote

- Salt to taste

Lightly toast the pumpkin seeds without burning them, and then use a chocolate mill to grind to the right consistency.

Hard boil the eggs, peel, and mash with a fork.

Boil the tomatoes in a 1 1/2 liters of water with salt, along with the habanero chiles, and epazote. When done, drain the tomatoes, seed them, and puré with a little salt.

Alternatively, you can puré the tomatoes and then prepare a fried salsa with the habanero chiles.

Moisten the ground pumpkin seed paste with the hot water used to cook the tomatoes and knead lightly, continuing to add moisture as needed until the seeds release their oil. Save the oil and serve as a condiment for the taquitos.

Add enough of the remaining liquid left from cooking the tomatoes to the ground pumpkin seed paste to make a sauce the consistency of slightly thick cream. Add a little salt, too.

Dip the warm tortillas in the pumpkin seed cream, place on a platter, fill each one with hard boiled egg, roll up, and top with the pumpkin seed cream, tomato salsa, and a little pumpkin seed oil.

[1] Zurita, Ricardo Muñoz, “Chile Verde,” Larousse Diccionario Enciclopédico de Gastronomía Mexicana (s.l.: Larousse, 2012): 343.