What Story Does a Cookbook Tell?

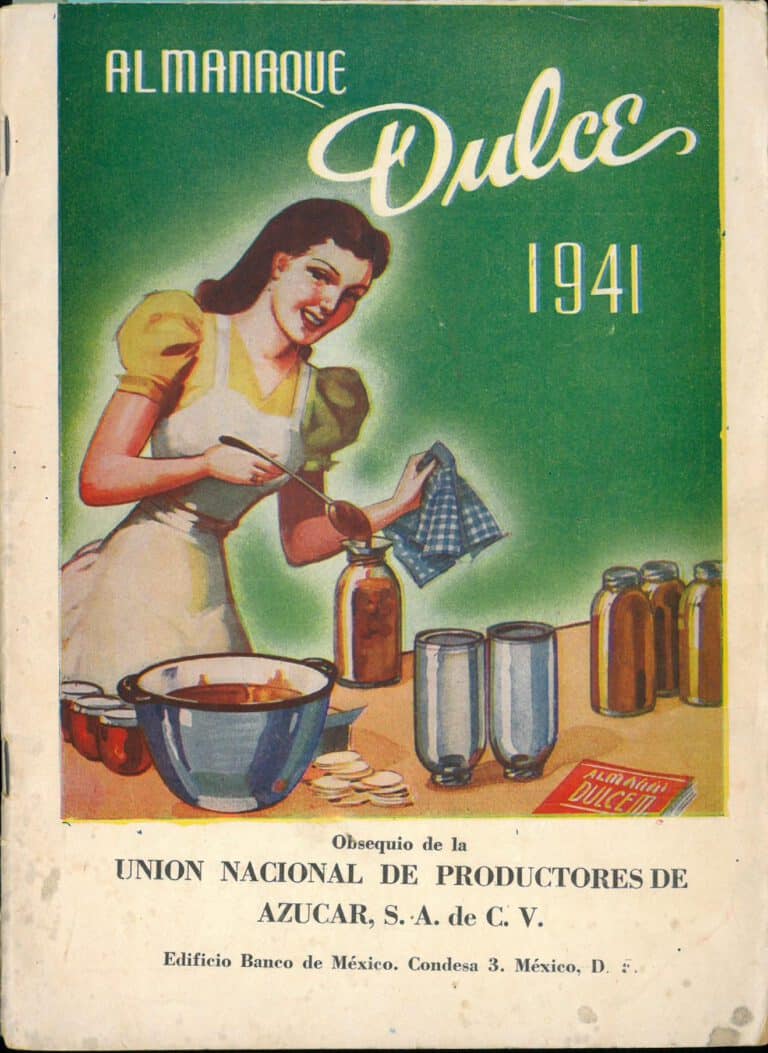

What can you do with a cookbook? The obvious answer is that you can find wonderful recipes to reproduce or modify in your own kitchen. Yet, cookbooks are so much more. For a graduate class that I am teaching in the history department at UTSA my students and I have been exploring the importance of cookbooks as primary sources for understanding the past. Historians see so much more than the recipes. Here, I will provide just one example of what a historian might focus on when interpreting a cookbook such as those in the UTSA Special Collections.

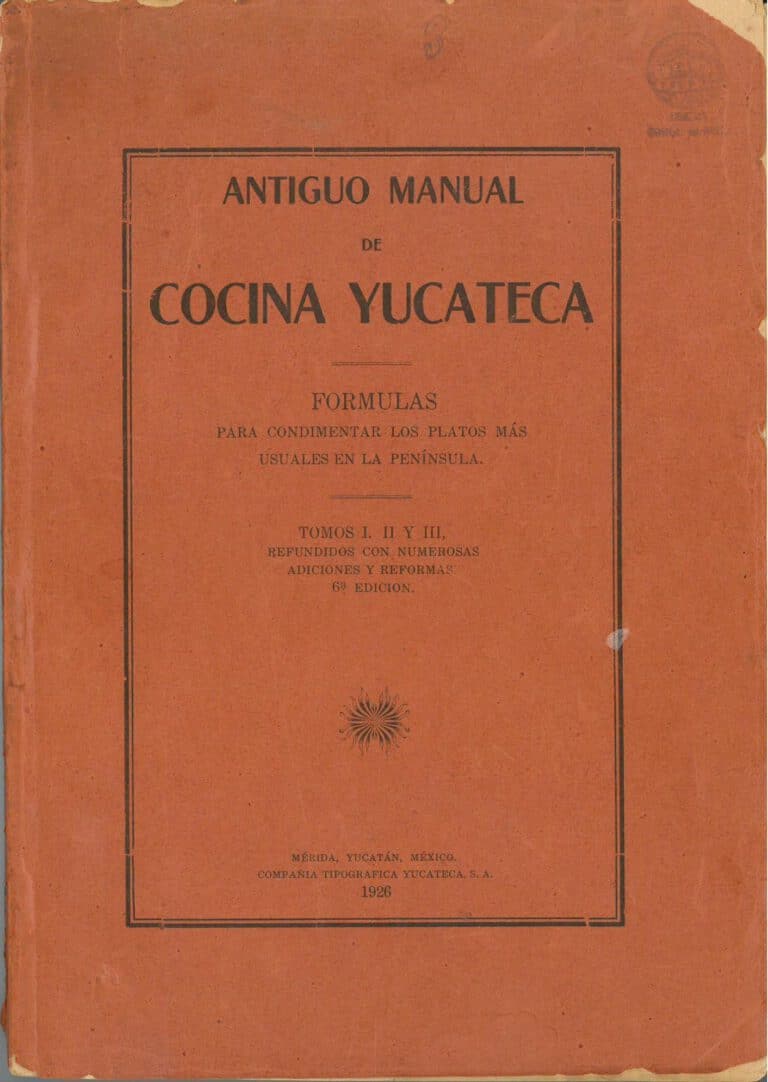

Historians look at recipes, of course, but they will also want to know something about the author of each cookbook as well as the book’s unique publishing history. We consider this critical for understanding the text. Cookbook authors are, generally, collectors of transmitted recipes. It is only in rare cases that the author is the creative inventor of a recipe. The author practices a degree of control over the recipe through their choices, but, in many cases, the author does not experiment with every recipe in the manual. So we want to know how close the author is to the subject that he or she is representing in the cookbook.

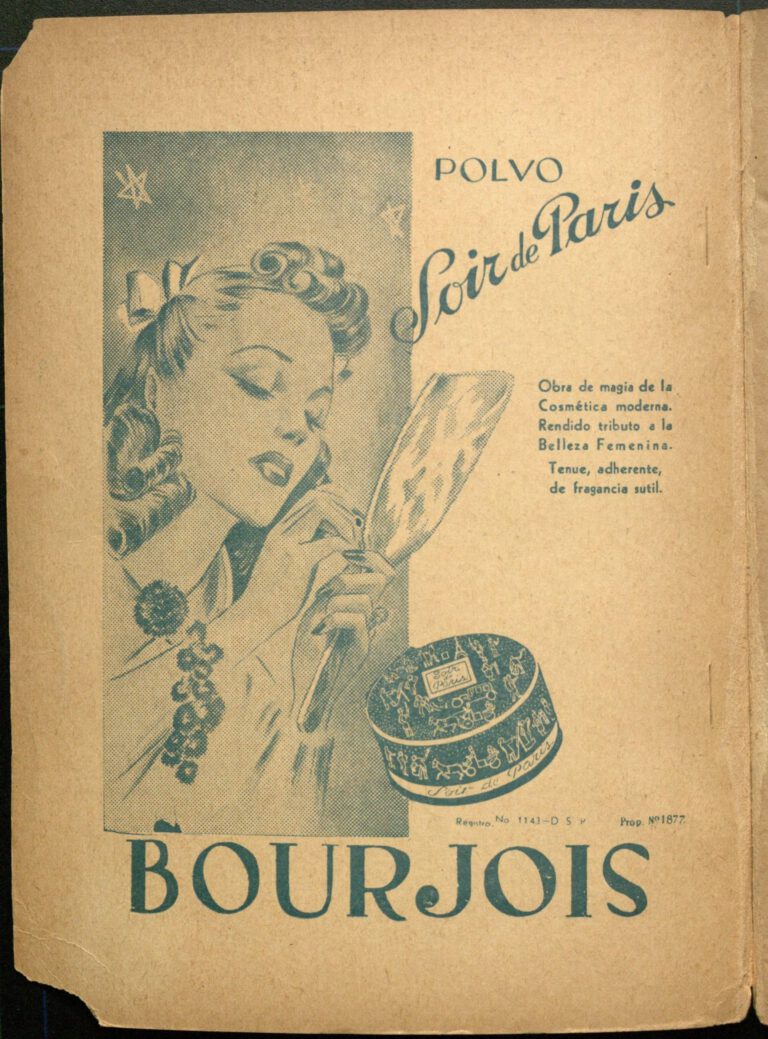

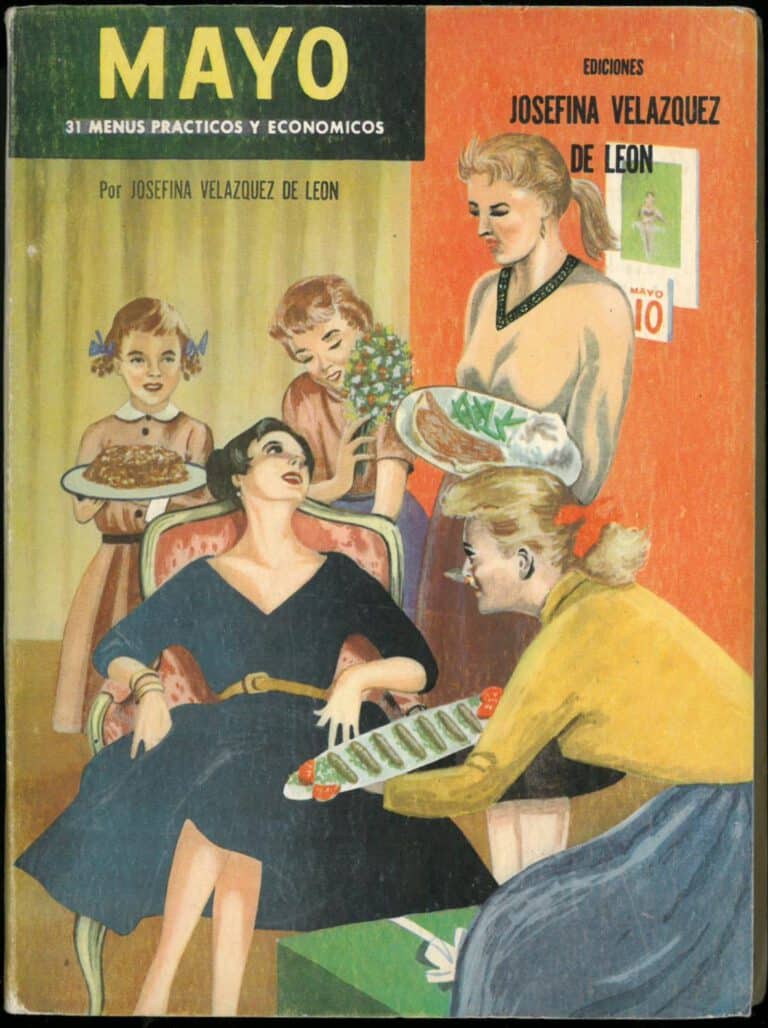

Given the critical role of the author in choosing recipes and filtering the instructions, historians will give particular attention to the author’s gender, education, social status, ethnic origin and language. In the days before celebrity chefs, cookbook authors often used pseudonyms or allowed institutions or companies to claim authorship. While the author might reveal something about their identity and recipe collection techniques in the ancillary texts, research is often required to uncover the author’s connection to the recipes presented in the manual as well as the circumstances of the book’s publication.

What difference can authorship make? We can see the importance in the work of on historian who set out to understand how frontier women cooked in early Canadian history. Historian Elizabeth Driver found two intriguing “frontier” cookbooks in the archives: Mrs. Clarke’s Cookery Book by Anne Clarke and The Cook’s True Friend by an author listed simply as Mrs. McDonald. Each book contained recipes for home cooks written in the 1880s. Neither book had an ancillary text to provide a context for the recipes.

Driver read each recipe carefully. She noted that there was something about the tone and extent of each author’s instructions that gave the impression that it was Mrs. McDonald who had the most personal experience in a rural, frontier kitchen. Further research on Mrs. McDonald revealed that she was, indeed, a stalwart member of her farming community who organized “socials” at her church where she collected recipes from other farm wives that would become the basis for The Cook’s True Friend. As for the author of the other cookbook, the existence of Anne Clarke remained elusive. Evidence from publication records suggested, however, that the book was compiled by a male tea merchant by the name of Charles Clarke who emigrated from England in 1881 and founded a cooking school in Toronto. Mrs. Clarke’s Cookery Book was mainly a series of recipes reproduced from the school’s training manual. Advertisements from Toronto newspapers show that the book was marketed to urban dwellers as a way to try their hand at authentic “frontier” cooking. There was no evidence that any of these recipes were collected by Anne Clark or originated on the “frontier.”

What did Driver make of this evidence? She concluded that it was Mrs. McDonald’s book that probably best represented what frontier women were cooking at the time of its publication. These were largely community recipes that represented the collected knowledge of the women in Mrs. McDonald’s social circle. Yet, Driver did not dismiss the importance of the cookbook by the non-existent Mrs. Clarke. Mrs. Clarke’s Cookery Book suggested that male authors lacked credibility as home cooks, at least enough so that Charles Clarke would hide his role in the origins of the cookbook. More importantly, she noted that the fact that urban dwellers were interested in trying to cook in a “frontier” style, which is evidenced by the sales of the book in urban areas, suggested that by the 1880s there was a certain romance in the Canadian imagination about life on the frontiers that intrigued people enough to want to try a version of that style of cooking in their city kitchens. In the end, both cookbooks were important texts that contributed to Driver’s understanding of what contributed to both the reality and the image of Canadian frontier cuisine.

Cooking manuals tell a story. Historians remind us that this story may be bigger than the sum of all the recipes.

One Comment